Macronutrients (i.e., carbohydrates, proteins, and fats) are generally understood concepts among the population, in which awareness is propagated through social media, online sources, DVDs, and class instruction (Johnston et al., 2014). There are also many nutritional approaches (i.e., Atkins, Zone, LEARN, and Ornish diets) that attempt to implement the aforementioned macronutrients to reach favourable weight loss, health, and performance outcomes (Gardner et al., 2010). Although macronutrients are foundational aggregates of a healthy diet, they are by no means the sole constituents of a well-balanced nutritional plan. In the following sections, I would like to consider water as another central nutrient in the human diet. Specifically, I would like to explore why adequate hydration is essential by reviewing complications that arise in the presence of deficiency, to better appreciate the need of maintaining fluid balance.

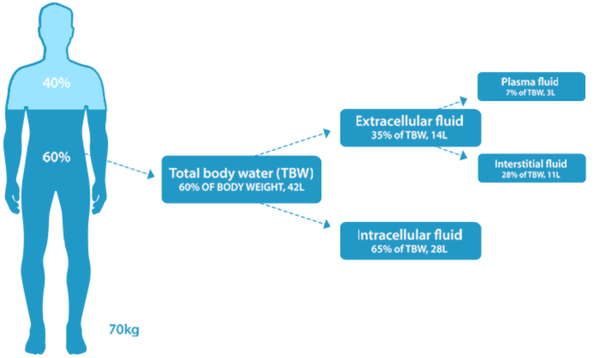

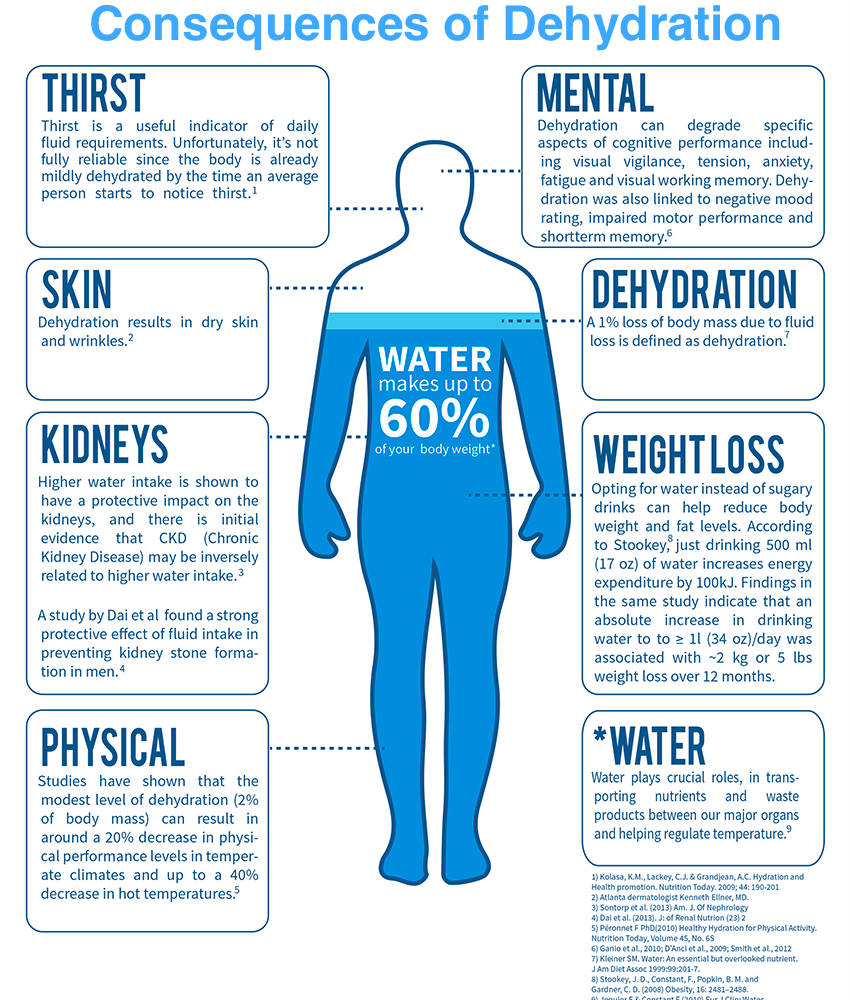

Humans are composed of approximately sixty percent water according to total mass, with no reserve in the body (Kavouras & Anastasiou, 2010). Thus, human sensitivity and reactivity to poor hydration can be serious, as evidenced by the body’s inability to survive beyond a few days without fluids (Maughan, 2012). Although it may be argued that the aforementioned example is both rare and extreme, there is evidence to suggest that both unfavourable and serious complications can be associated with chronic mild dehydration.

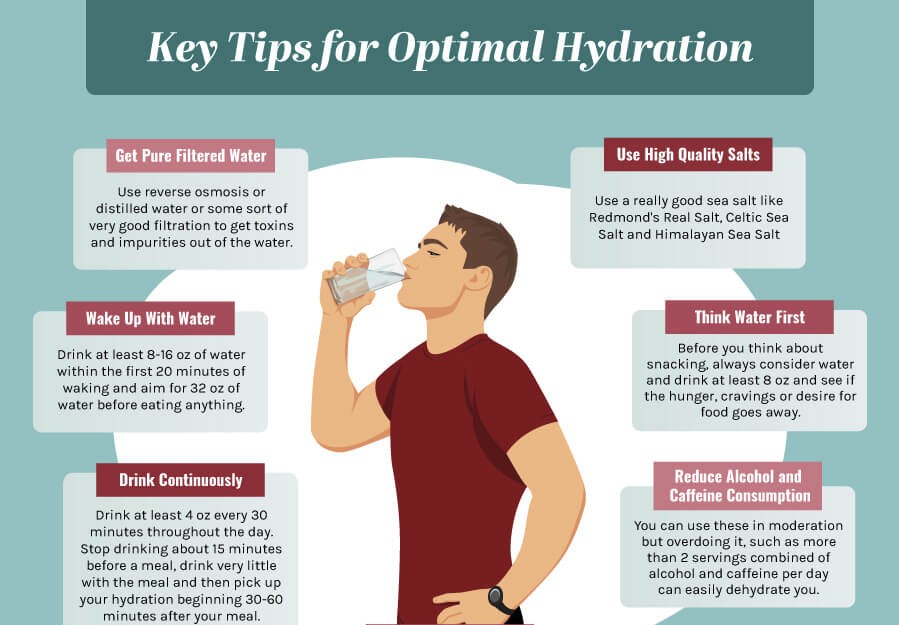

Optimal hydration, or fluid balance, might be defined as fluid intake matching fluid loss (Kavouras & Anastasiou, 2010). Such an equilibrium provides a fertile environment for several vital processes to occur; water plays a key role in digestion, absorption and transportation of nutrients, formation and stability of cell structures, removal of waste products and toxins, thermoregulation, and lubrication of joints and cavities (Kavouras & Anastasiou, 2010). When this equilibrium is disrupted, notable physiological aberrations occur.

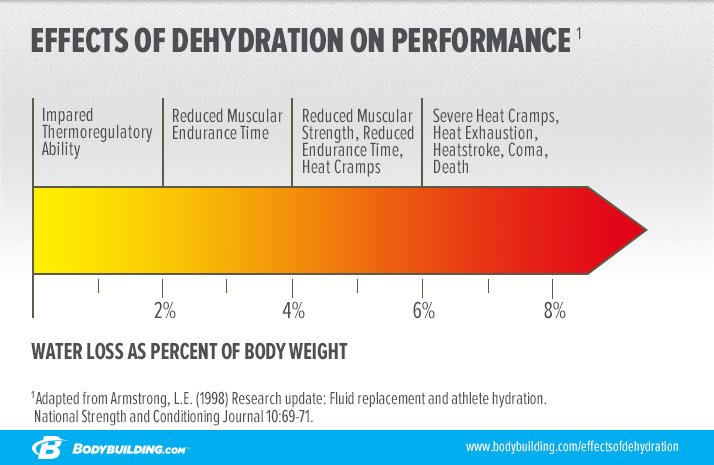

Mild dehydration, considered a four percent loss in bodyweight, can have undesirable effects on human performance (Kavouras & Anastasiou, 2010). Considered a small percentage of total body mass, performance measures can still change; endurance decreases, fatigue increases, and perceived effort increases (Popkin, D’Anci, & Rosenberg, 2010). Additionally, cardiovascular function and plasma volume can also drop (Kavouras & Anastasiou, 2010). Although the body compensates by increasing heart rate to maintain cardiac output, such a scenario may prove challenging long-term, and perhaps dangerous (i.e., to an individual with a pre-existing heart condition).

Mild and chronic dehydration has also been associated with decrements in cognitive function (Popkin et al., 2010). The authors noted that concentration, alertness, and short- term memory could be negatively effected in addition to perceptual discrimination, arithmetic ability, visuomotor tracking, and psychomotor skills (Popkin et al., 2010). Urolithiasis, commonly known as urinary stones, has been strongly associated with chronic mild dehydration (Popkin et al., 2010). The authors also noted that exercise induced asthma has equally strong associations to sub-par fluid intake (Popkin et al., 2010). Many other conditions (i.e., ketoacidosis, stroke, hypertension, dental diseases, urinary tract infections, gallstones, glaucoma, and mitral valve prolapse) also have associations to poor fluid intake. However, the evidence is presently considered both weak and speculative with the aforementioned conditions (Popkin et al., 2010).

In conclusion, water and fluid balance play centralized roles in key biochemical and physiological functions. Although the body has the capacity to adapt to short-term mild dehydration, more research has to be conducted on the long-term effects associated with many chronic conditions. Thus, until then, it may be prudent to encourage chronic fluid balance until we know more about the effects of chronic mild dehydration.

References

Gardner, C.D., Kim, S., Bersamin, A., Dopler-Nelson, M., Otten, J., Oelrich, B., & Cherin, R. (2010). Micronutrient quality of weight-loss diets that focus on macronutrients: Results from the A to Z study. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 92, 304-312.

Johnston, B.C., Kanters, S., Bandayrel, K., Wu, P., Naji, F., Siemieniuk, R.A., …Mills, E. (2014). Comparison of weight loss among named diet programs in overweight and obese adults. A meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association, 312(9), 923-933.

Kavouras, S.A., & Anastasiou, C.A. (2010). Water physiology. Essentiality, metabolism, and health implications. Nutrition Today, 45(6S), S27- S32.

Maughan, R., J. (2012). Hydration, morbidity, and mortality in vulnerable populations. Nutrition Reviews, 70, 152-155.

Popkin, B.M., D’Anci, K.E., & Rosenberg, I.H. (2010). Water, hydration, and health. Nutrition Reviews, 68(8), 439-458.

-Michael McIsaac