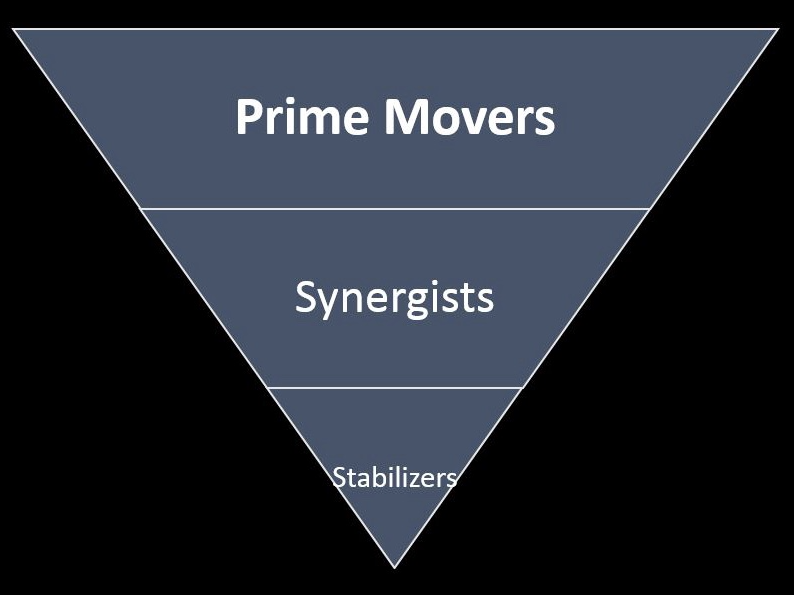

Movement assessments are intended to capture multiple muscle groups and joint actions, in addition to assessing the coordination of prime movers, synergists, and stabilizers (Page, Lardner, & Frank, 2010). They are also designed to break down the body into smaller “sections” by way of multiple, and smaller, movement patterns. Such an approach provides an opportunity of finding the causes of movement dysfunction, and pain, in a quicker and more efficient manner. As a means of appreciating and understanding Vladimir Janda’s assessment techniques, the following will consider the efficacy of his methods, and their groundings in evidence-based practice.

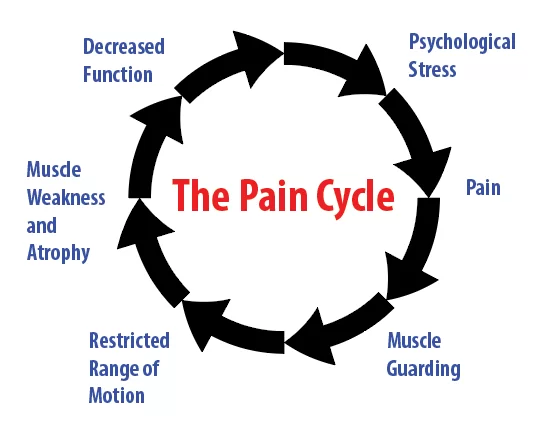

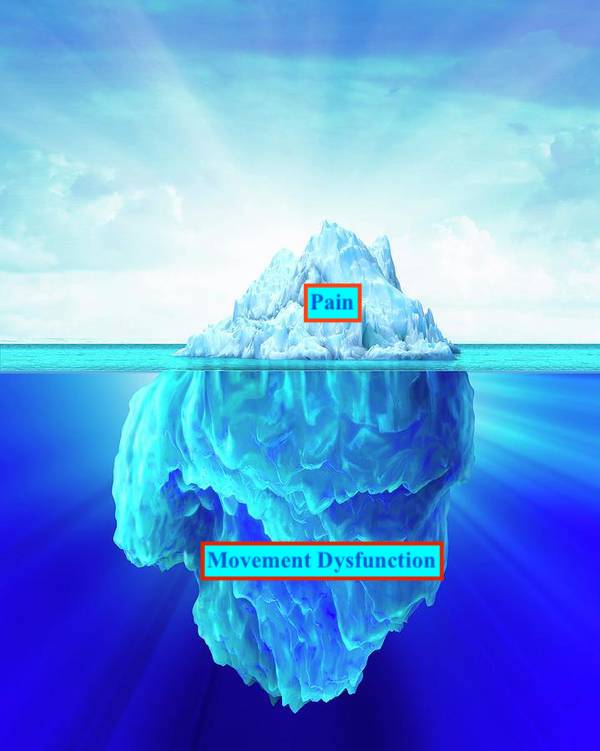

Janda’s underlying premise stated that movement dysfunction was derived from muscle imbalances and a compromised sensorimotor system (Page et al., 2010). Such physiological characteristics are thought to exacerbate dysfunction and pain, driving a cascade of events in the body known as the chronic musculoskeletal pain cycle (Page et al., 2010). The concepts of prime movers, synergists, stabilizers, and adaptations during exercise and movement are well understood (Kenney, Wilmore, & Costill, 2012). However, there are many different styles of movement assessments, begging the question of which is the most appropriate method. Weighing the value of any style of evaluation would then be, out of necessity, rooted in evidence-based research, best practice, and outcomes.

What appears evident is that Janda’s approaches are based on concepts such as coordinative structures, which suggest that the body controls multiple muscles and joints simultaneously to initiate and sustain movement (Magill, 2011). The aforementioned paradigm is applied in Janda’s assessments, as he acknowledged that basic movement patterns, contained within them, multiple muscles in the form of prime movers, synergists, and stabilizers (Page et al., 2010).

Janda’s basic movement pattern evaluations also implement a contemporary concept known as regional interdependence (RI), discussed in the author’s previous posts. Briefly, RI suggeststhat a remote dysfunctional movement pattern in one region of the body might influence a client’s primary report of pain and symptoms in a secondary region of the body (Sueki, Cleland, & Wainner, 2013). For example, Avrahami and Potvin (2014) found that their intervention group with tight hip flexor/painful low back experienced a small, yet significant, reduction in reports of pain after psoas lengthening. Such evidence supports the concept of RI, and Janda’s approach.

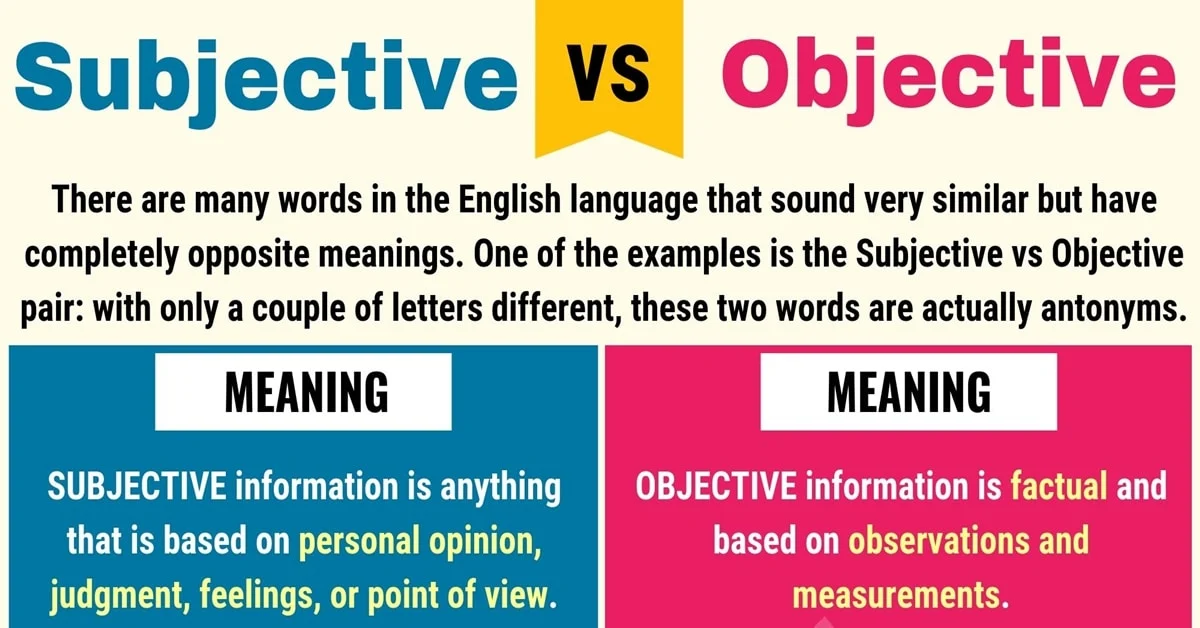

Although Janda’s assessments appear to be rooted in evidence-based research, motor control theory, and best practice, the author does have some mild, yet respectful, criticisms of his approach. Janda’s 6 assessments might be difficult to objectively quantify, as there are no scoring mechanisms in place. Thus, questions like “how bad is bad?” or “is the movement good enough?” may go unanswered. Another question the author has pertains to the transference/relevance of open kinetic chain (OKC) evaluations (i.e., hip extension test) to activities of daily living requiring a closed kinetic chain (CKC) event; the weight-bearing leg in the stance phase undergoes significant loading through the foot during the loading response phase to propulsion phase (Page et al., 2010). Thus, hip extension may behave differently in OKC versus CKC hip extension evaluations.

In conclusion, Janda challenged traditional structural approaches that often could not determine cause of pain and dysfunction (Page et al., 2010). Instead, he embraced the functional approach; a paradigm, which questioned the origins of pain and aberrant movement patterns. Although not a flawless system, Janda’s aggregate of best practice, and evidence-based research has helped provide a clearer roadmap to understanding the genesis of dysfunctional movement patterns, and functional pathology. Science, by its very nature, builds upon itself through the passage of time. Thus, it is equally likely that Janda’s evaluations will also grow and evolve into greater versions of itself, as more evidence and clinical practice culminates.

References

Avrahami, D., & Potvin, J.R. (2014). The clinical and biomechanical effects of fascial-muscular lengthening therapy on tight hip flexor patients with and without low back pain. Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association, 58(4), 444-455.

Kenney, W.L., Wilmore, J.H., & Costill, D.L. (2012). Physiology of sport and exercise (5thed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics

Magill, R. A. (2011). Motor learning and control: Concepts and applications (9thed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Page, P., Lardner, R., & Frank, C. (2010). Assessment and treatment of muscle imbalances: The Janda approach.Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Sueki, D.G., Cleland, J.A., & Wainner, R.S. (2013). A regional interdependence model of musculoskeletal dysfunction: Research, mechanisms, and clinical implications. Journal of Manual and Manipulative Therapy, 21(2), 90-102.

-Michael McIsaac