In past articles (please see links below), I have examined lifestyle, exercise, nutritional, and supplement interventions to support neurological conditions such as dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Emerging evidence is suggesting the potential efficacy of an eating protocol known as time-restricted feeding (TRF) to help manage such conditions. As a means of appreciating TRF and its relationship to neurological support, the following will consider most recent research findings, and potential mechanisms of action.

CANNABIS USE AND ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE AND GINKO BILOBA

ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE AND EXERCISE

ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE AND NUTRITIONAL SUPPORT

HEAVY METALS, HEALTH, AND SWEATING

SAUNAS, SWEATING, AND DETOXIFICATION

NIACIN (B3) DEFICIENCY: SYMPTOMS AND SOLUTIONS

INFLAMMATION AND ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE: CONNECTING THE DOTS

ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE AND INSULIN RESISTANCE

IMPROVING SLEEP QUALITY AND DURATION

IMPROVING SLEEP QUALITY AND DURATION WITH CBD/THC OIL

Balasubramanian et al1 stated that declining cerebrovascular health (lowered blood flow to the brain) has become a dominant driver, though not an exclusive cause, of age-related cognitive decline. Furthermore, it has been estimated that by the year 2050, more than 2.1 billion individuals will exceed the age of 60 years; an age which is a significant risk factor vascular cognitive impairment (VCI).1(2) Considering that other research has indicated particular nutritional interventions support and improve mental health/cognition (i.e., modulating neurogenesis, neuronal plasticity, brain signaling), TRF could be another vital intervention for neurological support.2

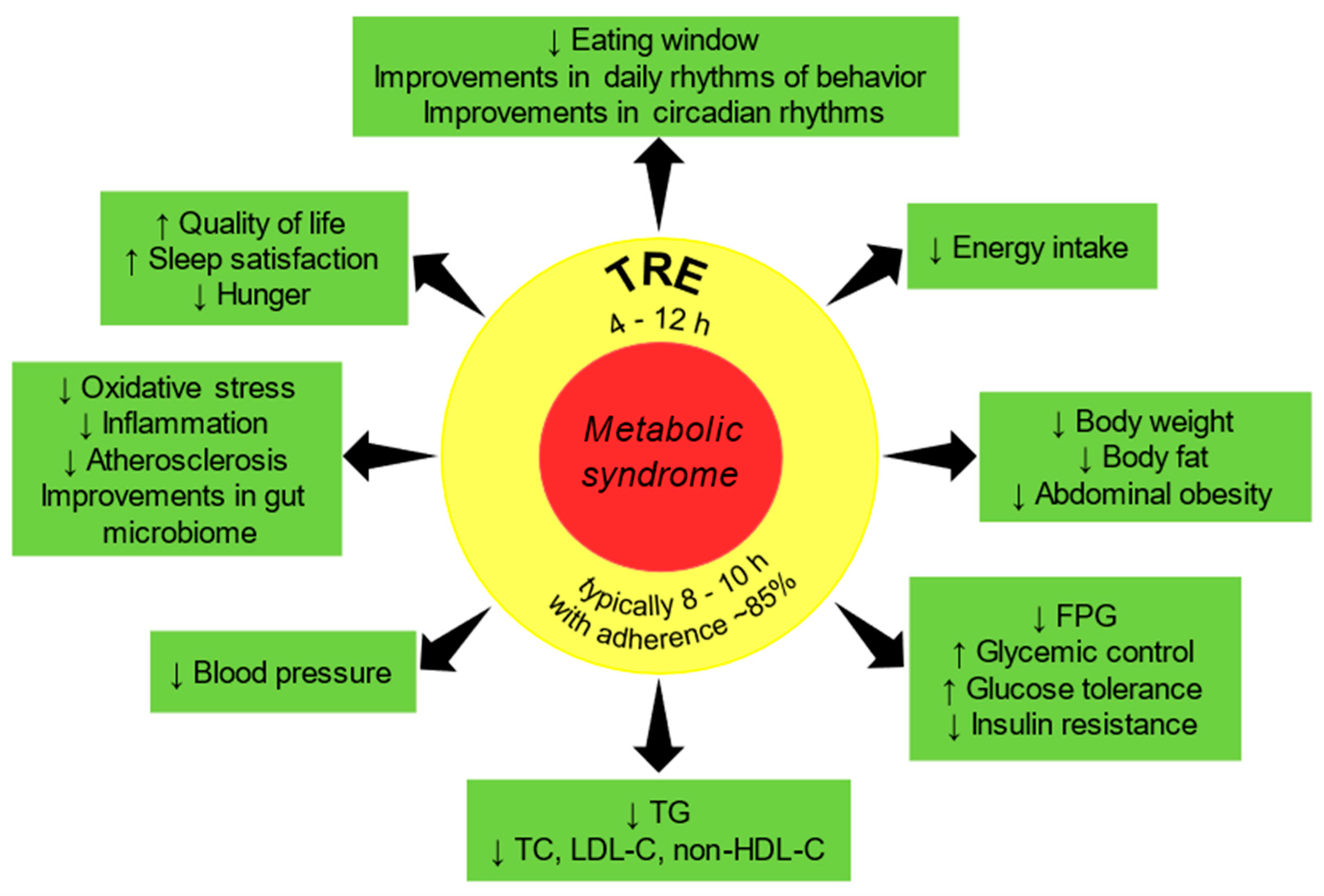

TRF can be defined as a form of intermittent fasting whereby food consumption/meals occur within a few hours of each other.2(2) Generally, all meals for the day are consumed between 6-10 hours.3 Beneficial outcomes from TRF include improvement in biomarkers such as reduced bodyweight, reduced fat mass, reduced blood pressure, and improved glucose tolerance.3(1) Furthermore, said outcomes occurred without a caloric restriction (CR); another protocol with beneficial effects, yet an intervention widely held as difficult to maintain.1(3) Thus, TRF is not a calorie deficit paradigm, but rather a pattern of eating.1(4)

Balasubramanian et al1(4) as well as Regimi and Heilbronn3(4,7) indicated that TRF had other benefits to include reduced oxidative stress, decreased inflammation, decreased triglycerides, improved insulin sensitivity, neuroprotective effects, improved redox status, and improvement in mitochondrial function. Part of said improvements may be derived from the extended period of hours not eating (14-18 hours); a condition, which may drive production of ketones for energy use.1(4) (Please see link below to ketones and health benefits).

ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE: A FUNCTIONAL MEDICINE APPROACH

The brain is rich in both oxygen and lipids; fertile precursors for oxidative stress and inflammation.1(5),4 Ultimately, oxidation and inflammation destroy blood vessels and neurons, which are exceedingly dense in the brain.1(5) Controlling underlying risk factors/drivers of oxidation/inflammation such as hyperinsulinemia, hyperglycemia, high blood pressure, and obesity would therefore appear relevant and prudent; TRF achieves such outcomes.5,6,7,8

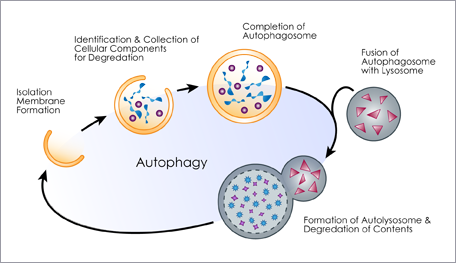

Interestingly, TRF may not only help control said risk factors; TRF may also help repair/recycle damaged cells (i.e., damaged proteins and organelles), a process known as autophagy.2(6) Currenti et al3(6) cited a study whereby 11 overweight adults participated in a TRF protocol. After only 4 days of TRF, researchers noted an increase in 6 genes, as well as SIRT1 and LC3A, all responsible for driving autophagy.3(6) Such processes are relevant because autophagy helps protect against diabetes, heart disease, cancer, and neurodegenerative diseases.3(6)

In conclusion, TRF is a pattern of eating whereby all food is consumed in a restricted window of time (i.e., 6-10 hours). Emerging evidence suggests that such a protocol helps control oxidative stress, inflammatory processes, and disease states closely associated with dementia. It is therefore possible that TRF, as part of a larger and more robust protocol, could help support neurological health, cognition, and overall quality of life with individuals experiencing/at risk of cognitive decline.

References

1. Balasubramanian P, DelFavero J, Ungvari A, et al. Time-restricted feeding (TRF) for prevention of age-related vascular cognitive impairment and dementia. Ageing Res Rev. 2020;64:1-22. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2020.101189.

2. Currenti W, Godos J, Castellano S, et al. Association between time restricted feeding and cognitive status in older Italian adults. Nutrients. 2021;13(1):1-11. doi:10.3390/nu13010191.

3. Regmi P, Heilbronn LK. Time-restricted eating: Benefits, mechanisms, and challenges in translation. 2020;23(6):1-11. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2020.101161.

4. Samina S. Oxidative stress and the central nervous system. J Pharmacol Ther. 2017;360(1):201-205. doi: 10.1124/jpet.116.237503.

5. Jayaraj RL, Azimullah S, Beiram R. Diabetes as a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease in the Middle East and its shared pathological mediators. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2020;17(2):736-750. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2019.12.028.

6. Lee HJ, Seo HI, Cha HY, et al. Diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease: Mechanisms and nutritional aspects. Clin Nutr Res. 2018;7(4):229-240. doi:10.7762/cnr.2018.7.4.229.

7. Pegueroles J, Jimenez A, Vilaplana E, et al. Obesity and Alzheimer’s disease, does the obesity paradox really exist? A magnetic resonance imaging study. Oncotarget. 2018;9(78):34691-34698. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.26162.

8. Tzourio C. Hypertension, cognitive decline, and dementia: An epidemiological perspective. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2007;9(1):1-8. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2007.9.1/ctzourio.

-Michael McIsaac