Iron deficiency anemia (IDA) is a leading cause of both infant morbidity and mortality worldwide (Zlotkin, 2003). Moreover, children moderately deficient in iron consumption may not only momentarily experience symptoms such as depressed mental and motor development; it may be irreversible (Zlotkin, 2003). Such a situation demands a preventative paradigm rather that reactive approach. The following sections will explore IDA manifestations in greater depth, in addition to presenting nutritional interventions to mitigate the condition.

As mentioned in the aforementioned section, infants who are iron deficient may present with altered behavior and cognition. Specifically, the infant may display increased fearfulness/wariness, irritability and unhappiness. Additionally, newborns may also have altered motor development, such as decreased exploration of environment, decreased willingness to leave a caregiver’s side, and increasing fatigue (Zlotkin, 2003). Left untreated, IDA will manifest in later years; children are more likely to repeat school grades or need special services. They may also have lower test scores of cognitive performance (Zlotkin, 2003). Zlotkin (2003) also stated that adolescents might have decreased verbal learning, memory, and lower standardized mathematics scores. Thus, it is essential to detect IDA early.

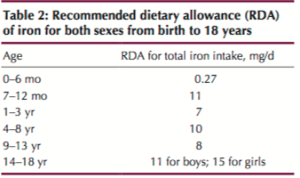

Zlotkin (2003) stated that during the early months of life human milk, which contains 0.2–0.3 mg/L of iron, does not provide enough iron to meet the demands of rapid erythropoiesis (production of red blood cells). Mobilization of iron within the infant’s body is essential because iron stores are generally depleted by 6 months of age. However, from 4 to 12 months after birth the infant’s blood volume doubles (Zlotkin, 2003). Thus, iron stores are mobilized within the infant’s body to meet said iron requirements. Ultimately, dietary sources of iron become critical to support the rate of red blood cell synthesis. Please refer to the table below outlining recommended dietary allowances of infants, children, and adolescents:

Three approaches can be utilized to help ensure adequate intake of iron: diversification of foods with bioavailable iron is essential, fortification of foods targeted to full-term infants and children, and supplementation (Zlotkin, 2003). Dietary diversification involves implementing a diet with a wider variety of naturally iron-containing foods, with particular emphasis on red meat, poultry and fish. Such foods have a high content of highly bioavailable heme iron (Zlotkin, 2003). Fortification of foods (see chart below), such as infant formula and cereals is another option. It should be noted, however, that this author has reservations of introducing cereals and processed foods (even if fortified with iron) due to high sugar and omega-6 content, which are associated with systemic inflammation and metabolic disease (Ilich, Kelly, Kim, & Spicer, 2014). Zlotkin (2003) suggested that iron supplementation would appropriate for individuals with anemia or communities of infants and young children who do not have readily available access to iron-fortified foods. When a soluble form of iron (such as ferrous sulfate or fumarate) is ingested in the proper dose, such an intervention is effective (Zlotkin, 2003).

In conclusion, IDA (when left untreated) can produce a myriad of unfavorable physiological and psychological conditions. However, if iron deficiency were controlled through nutritional interventions, such an approach would liberate the child from manifestations of the disease, while improving quality of life.

References

Ilich, J. Z., Kelly, O. J., Kim, Y., & Spicer, M. T. (2014). Low-grade chronic inflammation perpetuated by modern diet as a promoter of obesity and osteoporosis. Archives of Industrial Hygiene and Toxicology, 65(2), 139-148.

Zlotkin, S. (2003). Clinical nutrition: 8. The role of nutrition in the prevention of iron deficiency anemia in infants, children and adolescents. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 168(1), 59-63.

-Michael McIsaac