Individuals of advanced age (i.e., 65+) tend to exhibit changes in several biomarkers considered essential in maintaining activities of daily living (ADL) and overall health. Such changes include steady decrements in both muscle mass and bone density; hallmarks of the aging process.1 Left unchecked, such losses compound over time inexorably impeding individuals’ health and function. As a means of appreciating such alterations from aging, the following will consider the same in greater detail.

The muscular system accounts for approximately 40% of an individual’s overall body mass; a percentage underscoring its influence, and contribution to, bodyweight and function.1(347) As a result of said organ system’s sizable mass, skeletal muscle consumes 25% of total body protein synthesis per day.1(347) However, skeletal muscle begins a downward trend amongst individuals 50 years and older, at a rate of loss at approximately 1.5-5% per year.1(346) Such losses are also tightly correlated to strength losses, so much that a 15% decrease of strength is experienced and expected per decade of life.1(348)

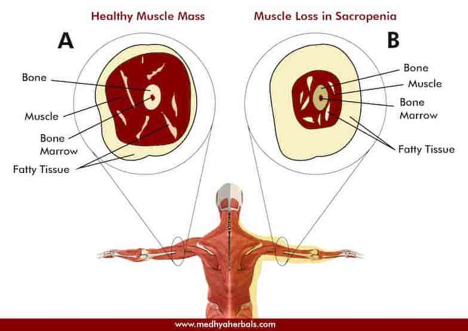

Mechanistically, Keller and Engelhardt1(348) stated that strength losses emanate from both a reduced number of muscle fibers and reduced muscle fiber size; two factors that, as an aggregate, deepen losses in function and ADLs.1(349) Moreover, strength losses increase the probability of muscle damage/accidents among the elderly and are further complicated by the tendency of muscle repair rates to decrease with age.1(349) Finally, decrements in muscle fiber size and number occur predominantly within type 2 fast twitch fibers; those whose main contribution fall within the realm of force production.1(349)

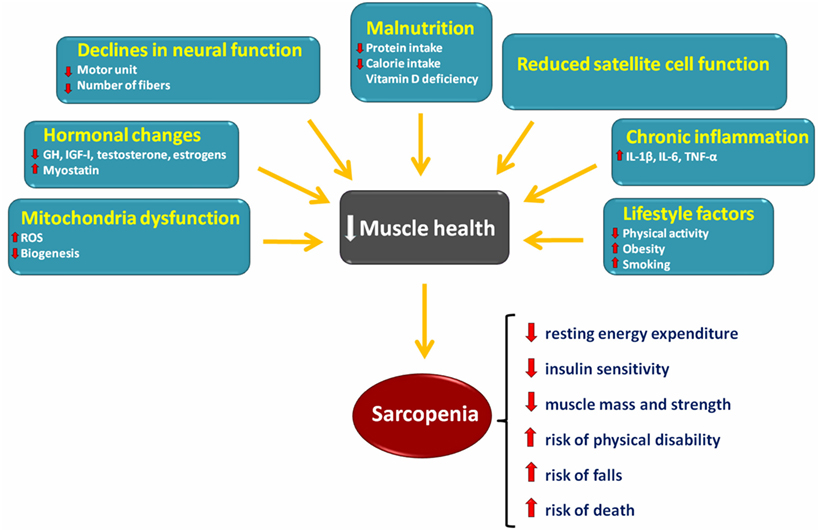

The physiological changes mentioned in the aforementioned sections are ultimately known as sarcopenia; a condition characterized, and diagnosed, by the incremental and progressive loss of skeletal muscle mass, strength, and physical performance among the elderly.1(349) The primary driver of said changes is a general lack of physical activity.1(349) Secondary contributors of said condition includes a lack of appetite (especially from low protein intake) amongst said population, which contributes to malnutrition.1(349) Please read The Elderly: Optimal Protein Sources and Consumption for more details.

In conclusion, individuals of advanced age (i.e., 65+) tend to exhibit changes in several biomarkers considered essential in maintaining ADLs and overall health. Such changes include steady decrements in both muscle mass and bone density; hallmarks of the aging process. Left unchecked, such losses compound over time inexorably impeding individuals’ health and function. Although sarcopenia can have devastating consequences among individuals afflicted with said condition, one pertinent solution does exist to counteract such changes; strength training. In upcoming articles, this author will explore such an intervention in greater detail.

References

1. Keller K, Engelhardt M. Strength and muscle mass loss with aging process. Age and strength loss. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2014;3(4):346-350. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3940510/. Published February 24, 2014. Accessed August 6, 2021.

-Michael McIsaac